I’m officially outing myself. I am a Slop Master…

Introduction

I bit my tongue. That’s the pathetic truth of it.

A family member was holding court about “AI slop”; how it’s ruining the internet, how it’s lazy, how it’s not real creativity. And I just sat there. Didn’t say a word. Didn’t mention that I’ve built five iOS apps using AI. Didn’t mention the art galleries on my website. Didn’t mention the stories I’ve written, the concepts I’ve explored, or the fact that AI gave me back a creative life I thought I’d lost.

I stayed silent because I was ashamed. Because somewhere in my gut, I’d internalized the idea that what I was doing was lesser. That using AI made me a fraud. That I should apologize for the tools I chose.

But I’m done with that. I’m done being quiet. And if what I make is slop, then call me the Slop Master, because I’m not apologizing anymore.

This essay exists because of an article in MIT Technology Review titled “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love AI Slop” by Caiwei Chen. It’s a thoughtful, generous piece that examines AI-generated content not as the death of creativity but as the messy birth of something new. Reading it crystallized something for me: we need more voices in this conversation. Not the hype-mongers selling AGI salvation, and not the doomers (←— speaking of “slop”) predicting the end of art; but people like me, who are actually making things with these tools and have something to say about it.

I have a platform. A blog I wouldn’t have even bothered with before AI gave me a reason to write. So why not add my voice? Why not stand up and say: the “slop” discourse is broken, intellectually lazy, and needs to be confronted…

I. THE SLOP TRAP: How a Lazy Term Killed the Conversation

Here’s what “AI slop” does: it lets you dismiss an entire category of creative work without engaging with it. It’s a thought-terminating cliche, a verbal shortcut that replaces critique with disgust. You don’t have to think about whether a specific piece is good or bad, interesting or boring, thoughtful or thoughtless. You just slap the “slop” label on it and move on, secure in the knowledge that you’ve signaled your taste.

It’s aesthetic gatekeeping masquerading as quality control.

The term itself has a fascinating lineage. As Chen’s article notes, “slop” traces back to early-2010s 4chan culture; a forum notorious for its insular, toxic in-jokes. Over time, it evolved into a catch-all pejorative for low-quality mass production. Now it’s been weaponized against AI-generated content specifically, becoming shorthand for “bad because AI made it.”

The Cambridge Dictionary recently added a new definition: “content on the internet that is of very low quality, especially when it is created by AI.” Notice the structure of that definition. Not “low-quality AI content,” but “low-quality content, especially AI.” The tool itself becomes evidence of the crime.

This is the trap: the method becomes the verdict, not the result.

You see a piece of AI-generated art, a story, a video. You don’t ask: Is this interesting? Does it succeed at what it’s trying to do? Does it make me feel something? Instead, you ask: Was AI involved? And if the answer is yes, the conversation ends. It’s slop. Case closed.

But here’s the thing: this logic is broken, and it’s always been broken.

Let’s explore the logic.

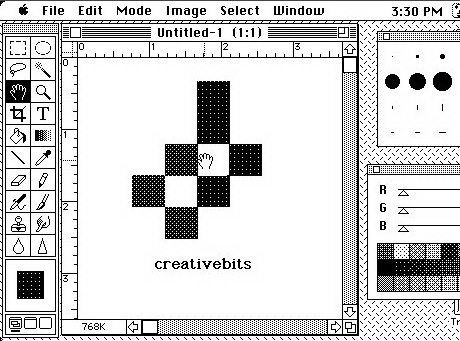

Imagine someone shows you a digital painting. Vibrant colors, strong composition, emotional weight. You’re moved by it. Then they tell you it was made in Photoshop.

Do you suddenly dismiss it? Do you say, “Oh, that’s just pixel-pushing slop. Not real art”?

No? Good. Because that would be absurd.

Now go back twenty years. Show that same painting to a traditional artist in the early 2000s, and there’s a non-zero chance they would dismiss it. “Digital art isn’t real art. It’s cheating. The computer does all the work.”

I’m not making this up. I was an avid Photoshop user during this era, and you can still find archived posts of the arguments about it in forums; artists arguing passionately that digital tools undermined the craft, that Photoshop was a crutch, that “real” artists used canvas and paint. One commenter on a 2014 blog post captured it perfectly: “Pencil is a tool just like a Wacom tablet and Photoshop are tools… but many people drawing traditionally still don’t accept digital art as ‘real art.’”

Sound familiar?

Now go back further. Photography in the 1800s. When the daguerreotype was invented, painters lost their minds. The French poet Baudelaire called photography “art’s most mortal enemy,” arguing that it was mere mechanical reproduction; no soul, no vision, no craft. Just point and click. Anyone could do it.

“Where’s the skill?” they asked. “Where’s the human touch?”

And yet. Photography didn’t destroy painting. It became its own art form. It democratized portraiture, yes; but it also gave us Ansel Adams, Diane Arbus, Henri Cartier-Bresson. It created entirely new ways of seeing.

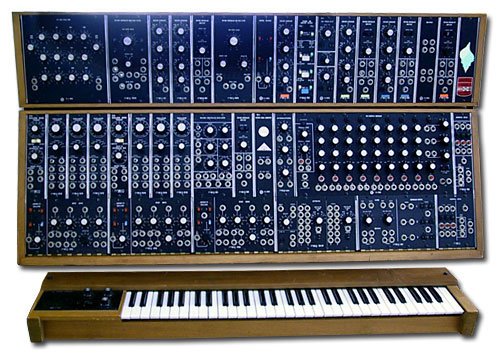

The synthesizer. Musicians in the 1960s and 70s sneered at electronic instruments. “That’s not real music. Real musicians use real instruments.” The Moog was cheating. Drum machines killed session drummers. And now? Synthesizers are venerated, iconic, essential. They are the sound of entire genres.

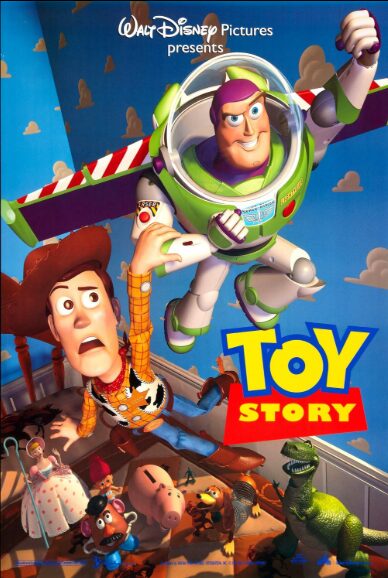

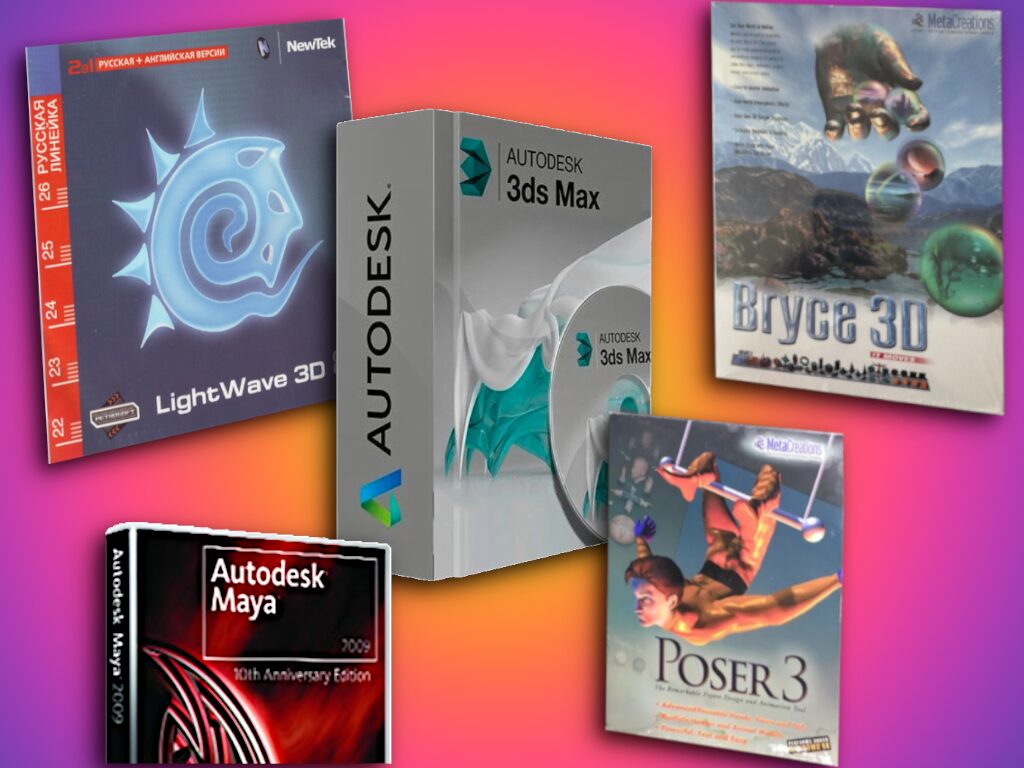

3D rendering. When Pixar released Toy Story in 1995, practical effects purists declared that CGI looked “fake and soulless.” Real filmmakers used miniatures, puppets, physical sets. And now? Every blockbuster, every AAA video game, every high-budget production uses 3D rendering as standard. It’s taught in film schools. It’s the industry.

Every. Single. Time.

Every time a new tool emerges that makes creation easier or more accessible, the gatekeepers declare it illegitimate. They say it’s “not real art” because it doesn’t require the right kind of suffering, the right kind of effort. And every single time, they’re wrong. The tool becomes standard. Then it becomes venerated. Then it becomes nostalgic.

AI is just the latest chapter in this exhausting, predictable book.

But here’s what makes the “slop” discourse particularly insidious: it doesn’t just dismiss the tool; it dismisses the people using it.

When you call something “slop,” you’re not making a critique. You’re not saying, “This specific piece fails because of X, Y, Z.” You’re saying, “This entire mode of creation is unworthy of serious consideration.” You’re saying, “The people making this stuff aren’t real creators.”

And that’s where I draw the line.

Because I know exactly what AI has given me. It gave me the ability to code, something I’d dreamed of for years while working in IT but couldn’t figure out how to approach. I now have five apps on the App Store. They’re not popular, but they exist. They solve real problems. They represent concepts I’m proud of.

AI gave me the ability to write stories. I’ve completed three short stories that have been critically reviewed by my wife and daughter. Before AI, I wouldn’t have bothered. My neurodivergence gets in the way of evolving a narrative from concept to start to finish. I couldn’t hold the whole structure in my head. But with AI as a collaborative partner? I could.

AI gave me back visual art. I have five galleries on my personal site (nulljoy.com). Images that explore concepts I never would have bothered to articulate alone. The collaboration revealed things I didn’t know I was trying to say. I was a Photoshop professional for about a decade and a half, but I lost my way.

II. TOOL PANIC: A History of Artistic Amnesia

Let’s get specific about the pattern, because it’s important to see how predictable this is.

Photography (1839-1900s): “Not Real Art”

When Louis Daguerre introduced the daguerreotype in 1839, it was a revolution… and a threat. For the first time, you could capture a likeness without spending hours painting. Portraitists panicked. What would happen to their livelihoods? What would happen to art itself? (OH the humanity!)

Charles Baudelaire, one of the most influential critics of his era, wrote in 1859 that photography was “the refuge of every would-be painter, every painter too ill-endowed or too lazy to complete his studies.” He declared it a soulless reproduction, incapable of capturing truth or beauty. It was mechanical. Automatic. Anyone could do it.

“Where’s the skill?” they asked. “Where’s the craft?”

The argument was that photography democratized image-making in a way that undermined the value of “real” artistry. If anyone could push a button and get a result, what did that mean for the people who’d spent years mastering oil painting?

And yet. Photography didn’t kill painting. It freed it. Painters no longer had to be photorealistic; they could explore abstraction, impressionism, expressionism. Photography became its own art form, with its own masters, its own techniques, its own capacity for emotional truth.

But that transition took decades. And during those decades, photographers had to endure being called hacks, frauds, and button-pushers.

Sound familiar?

Synthesizers (1960s-1980s): “Not Real Music”

When Robert Moog introduced his modular synthesizer in the 1960s, musicians were split. Some saw potential. Others saw heresy.

Electronic music wasn’t “real” music, they said. Real musicians played instruments; guitars, pianos, horns. Things you had to practice for years to master. The synthesizer was a shortcut. It was cheating. And worse, it was killing jobs. Session drummers complained that drum machines were replacing them. Bassists worried about sequencers.

The criticism wasn’t just about aesthetics; it was about labor, identity, and what it meant to be a musician.

And now? Synthesizers are iconic. They define entire genres: electronic, synthwave, industrial, ambient. Artists like Charanjit Singh, Kraftwerk, Brian Eno, and Wendy Carlos are legends. The Moog is a museum piece. Vintage synths sell for thousands of dollars.

The tool that was once dismissed as fake is now venerated as essential.

(I owned an MC505 “Groovebox” in the late 90’s, early aught’s. Awesome box. Much fun!)

Digital Art and Photoshop (1990s-2000s): “Not Real Art” (Again)

In the 1990s and early 2000s, as digital art tools became accessible, traditional artists pushed back. Hard.

“Real artists use paint and canvas,” they said. “Digital is cheating. The computer does all the work. There’s no skill involved; it’s just filters and undo buttons.”

I found a blog post from 2014 where a digital artist recounts showing his work to older artists and teachers, only to have them roll their eyes. “Like I was this huge fake,” he writes. He describes the frustration of being dismissed simply for the tools he used, not for the quality of his work, but for the method.

Another commenter on that same post: “Traditional vs Digital is a dumb debate. Pencil is a tool just like a Wacom tablet and Photoshop are tools.”

Exactly.

And now? Digital art is the industry standard. It’s taught in art schools. Concept artists, illustrators, and designers all use Photoshop, Procreate, Clip Studio Paint. The divide has evaporated. The tool is just a tool.

But it took years for that shift to happen. And in the meantime, digital artists had to deal with being called fakes.

3D Rendering (1990s-2010s): “Looks Fake and Soulless”

When Pixar released Toy Story in 1995, it was groundbreaking… and controversial.

Directors like Christopher Nolan and Guillermo del Toro have famously championed practical effects over CGI, arguing that there’s a tactile reality to physical models that digital can’t replicate.

And you know what? They’re not wrong. Practical effects do have a unique quality. But that doesn’t make CGI illegitimate. It just makes it different.

Now, CGI is ubiquitous. It’s in every Marvel movie, every AAA video game, every high-budget production. Pixar is a cultural institution. ILM (Industrial Light & Magic) pioneered techniques that are now industry standard. (Don’t get me wrong.. CGI is ABUSED these days, really… there are many times where it is unnecessary, but that doesn’t invalidate it.)

The tool that was once dismissed as fake is now foundational.

Do you see the pattern?

Every new tool that makes creation easier gets accused of being:

- Too easy (“Anyone can do it”)

- Soulless (“The machine does all the work”)

- Not real art (“Real artists use X”)

And every single time, the critics are proven wrong. The tool doesn’t destroy the craft, it expands it. It creates new forms, new aesthetics, new possibilities.

AI is no different. It’s just the latest iteration of a story we’ve seen before.

And yet, here we are again, acting like this time it’s actually different. This time, the tool really will ruin everything.

That’s BS.

III. THE INTERNET IS ALREADY SLOP (And You’re Still Here)

Let’s talk about an elephant in the room: the internet has always been garbage.

Not all of it, obviously. But the vast majority? Yeah. Garbage.

Sturgeon’s Law, formulated by science fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon in the 1950s, states: “90% of everything is crap.“ He was talking about science fiction, but the principle applies universally. Most things; books, movies, music, art, websites, are mediocre at best. That’s just how it works. The good stuff is rare. It always has been.

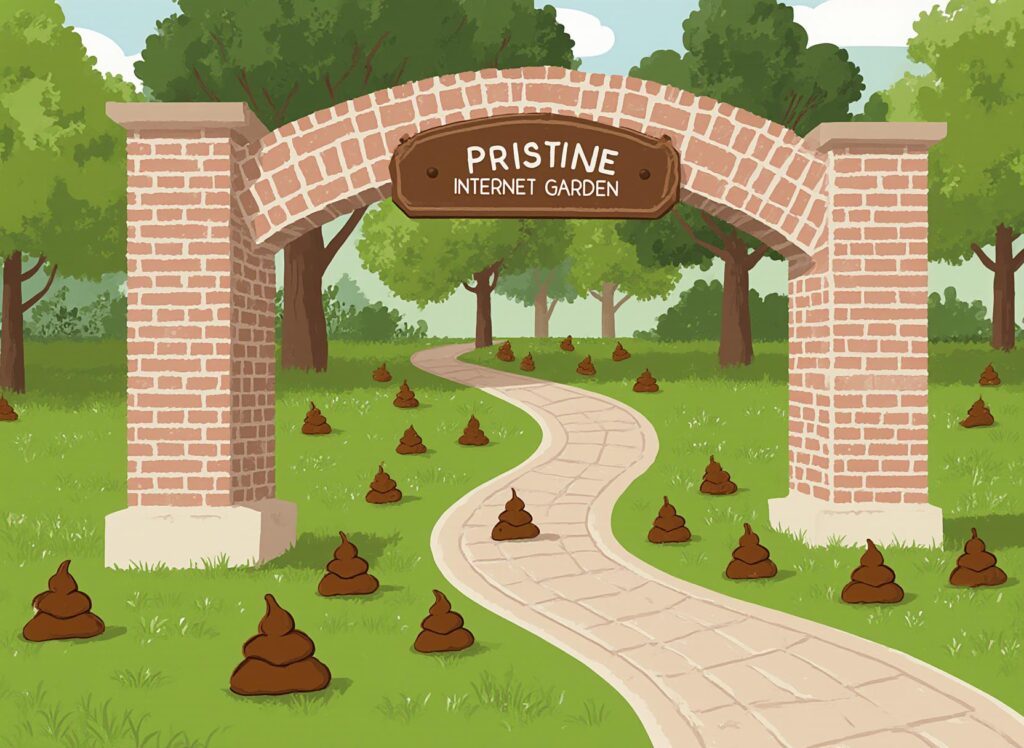

And yet, the “AI slop” discourse acts like AI invented low-quality content. Like the internet was some pristine garden of thoughtful expression before ChatGPT showed up.

Are you kidding me?

The internet has been a content mill for decades. Let me remind you what was already out there:

- SEO-farmed listicles: “10 Ways to Boost Your Productivity (Number 7 Will Shock You!)”

- Stock photo blogs: Generic advice wrapped around generic images, designed to rank on Google and serve ads.

- Endless Reddit reposts: The same meme, reposted 47 times across 12 subreddits.

- Clickbait headlines: Engineered to trigger outrage, curiosity, or FOMO.

- Influencer spam: “Swipe up to get 10% off this thing I definitely use and definitely didn’t just get paid to promote.”

- Your cousin’s unsolicited vacation photos: Look, I’m happy you went to Cancun, but I didn’t need to see 84 pictures of the same beach… Also, men shouldn’t wear thongs on public beaches.. : /

Is that last one slop? Or is it beloved personal content? Where’s the line?

The point is: AI didn’t create slop. It just made it faster.

And here’s the kicker: you’re still here. You’re still scrolling. You’re still on TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, Reddit. You’re still wading through the garbage to find the 1% that’s actually interesting, funny, or meaningful.

Because that’s how the internet has always worked. It’s a firehose of content, and your job as a user is to filter. Some of it’s good. Most of it’s not. But you keep coming back because sometimes you find something that makes it worth it.

AI-generated content operates on the exact same logic. Most of it is forgettable. Some of it is genuinely compelling. And the fact that it was made with AI doesn’t change that calculation.

The “slop” discourse is selective outrage. It’s not actually about quality, it’s about who gets to make things and how much effort you think they should have to expend.

If a 15-year-old makes a funny video using their phone and a free editing app, is that slop? Or is it creative expression?

If a solo developer builds an iOS app using AI to write the code, is that slop? Or is it resourcefulness?

If an artist uses Midjourney to explore visual concepts they couldn’t afford to commission, is that slop? Or is it democratization?

The answer depends entirely on whether you think the creator “deserves” to have made the thing. And that’s where the gatekeeping comes in.

Because let’s be honest: when people say “AI slop,” what they often mean is, “This person didn’t suffer enough to earn my respect.”

They didn’t spend years in art school. They didn’t learn to code from scratch. They didn’t pay their dues.

But who decided that suffering was a prerequisite for creativity? Who decided that the only valid art is art that required pain?

Eff that elitism.

Let me be clear: I’m not saying all AI content is good. I’m not even saying most of it is good. I’m saying the method of creation is not a valid basis for dismissing it outright.

Judge the work. Not the tool.

And if you can’t do that, if you can’t engage with a piece on its own terms without first asking, “Was AI involved?”, then you’re not critiquing. You’re just performing disgust to signal your taste.

IV. ECONOMICS VS. AESTHETICS: Separate the Fears

Let’s acknowledge another elephant in the room that I’ve been dancing around: Yes, AI will displace some jobs. This is real. This is painful.

Artists, writers, illustrators, voice actors, coders; people are scared, and they have every reason to be. When a tool can generate serviceable stock images in seconds, what happens to the stock photographer? When an AI can write ad copy, what happens to the junior copywriter? When it can produce background music, what happens to the composer trying to break into the industry?

These are legitimate concerns. Labor anxiety is not the same as aesthetic critique, and conflating the two is intellectually dishonest.

So let’s separate them.

The Economic Reality

A Brookings Institution study examined freelance marketplaces after generative AI tools launched in 2022. They found that freelancers in “AI-exposed occupations” saw approximately:

- 2% decline in contracts

- 5% drop in earnings

(Current metrics are so mired by the HYPE machine, that they are to un-reliable to repeat.)

That’s not catastrophic, but it’s not nothing either. And it’s early days… these numbers could get worse.

I’m not here to pretend this isn’t happening. I’m not going to gaslight people who are watching their job prospects shrink in real time. That would be cruel and stupid.

But here’s what I will say: the economic anxiety is valid, but it’s being weaponized to shut down a conversation that has nothing to do with labor displacement.

When someone creates an AI-generated video for fun, posts it on TikTok, and gets called out for making “slop,” that’s not a labor issue. That person isn’t taking a job from a professional animator. They’re just… creating something.

When I use AI to build apps I couldn’t have coded otherwise, I’m not displacing a professional developer, I was never going to hire one. I didn’t have the budget. I didn’t have the connections. I was locked out of that form of creation entirely.

AI didn’t replace a human in my case. It gave me access to a skillset I never had.

The Sleight of Hand

Here’s the trick: people use “this AI art sucks” as a stand-in for “I’m worried about my livelihood.”

But those are two completely different statements.

One is an aesthetic judgment. The other is an economic concern. And conflating them lets you dodge the harder conversation about what we actually owe each other as technology changes.

You can support:

- Universal Basic Income

- Stronger labor protections

- Regulations on how AI training data is sourced

- Compensation models for creators whose work was used in training sets

AND you can acknowledge that AI tools enable new forms of creativity for people who were previously excluded.

These positions are not contradictory. You don’t have to choose between protecting workers and allowing new creators to emerge.

But the “slop” discourse collapses that nuance. It treats all AI-generated content as an enemy, regardless of context, regardless of intent, regardless of who’s making it or why.

Who Gets to Create?

This is where the economic argument reveals its gatekeeping core.

Because if your position is “AI is bad because it lets people create without traditional skills,” then what you’re actually saying is: “Some people don’t deserve access to creative tools.” (Oops.. did some of you just slink lower in your seats??)

You’re saying the three-fingered painter shouldn’t get to paint because they can’t hold a brush.

You’re saying the neurodivergent or dyslexic writer shouldn’t get to tell stories because they struggle with narrative structure and composition.

You’re saying the broke or working-class kid who can’t afford art school shouldn’t get to make art because they don’t have the right credentials.

And you’re justifying that exclusion by wrapping it in concern for professional artists.

But let me be very clear: I am not a corporation strip-mining creative labor for profit.

I’m a solo developer. I was locked out of coding and writing, most of my life; not because I lacked creativity, but because I lacked the technical execution skills that traditional tools required.

AI didn’t replace a human in my workflow. It replaced nothing, because I wasn’t creating before.

So when people tell me I’m “taking opportunities away from real artists,” what they’re really saying is: “You shouldn’t be allowed to create at all.”

The Real Question

Here’s what the discourse should actually be asking:

Is the goal to protect existing creators, or to prevent new creators from emerging?

Because those are not the same thing.

If you want to protect professional artists, advocate for:

- Fair compensation when their work is used in training data

- Legal frameworks that require consent and attribution

- Economic safety nets for workers displaced by automation

But if your solution is “no one should use AI to create,” then you’re not protecting artists, you’re protecting exclusivity.

And exclusivity has never been a virtue.

V. THE REPLICATION PROBLEM: Where the Line Actually Is

Alright. Let’s talk about where I draw the line.

Because I’m not here to defend all AI-generated content. Some of it is genuinely bad. Some of it is thoughtless. Some of it is exploitative.

And I want to be very clear about what separates thoughtful creation from actual slop.

The Slop Camps

There are groups of people, let’s call them the “slop camps”, (you may know them as Content Mills) who are copying any good idea, replicating it badly, and churning it out for clicks, ad revenue, and algorithmic engagement.

These are the bastards who:

- See a viral AI video concept and immediately pump out 50 variations with zero iteration

- Use AI to generate clickbait thumbnails designed purely to game YouTube’s algorithm

- Create fake “street interview” videos with AI-generated faces, posting them en masse across TikTok

- Spam low-effort AI art onto DeviantArt, ArtStation, and NFT marketplaces with no curation, no refinement, no thought

This is actual slop.

Not because it’s AI-generated, but because it’s thoughtless replication with no stake in the outcome.

There’s no vision. No iteration. No care. Just: generate, post, monetize, repeat.

The difference isn’t the tool, it’s the intent and the effort.

The “Just Type a Prompt” Myth

One of the most infuriating dismissals of AI-assisted work is the idea that it’s effortless.

“You just type a prompt and boom, art!”

Bull, and also, just NO…

Yes, AI tools are capable. Astonishingly so. But they are not easy when you have a specific vision.

Getting an AI to execute exactly what’s in your head requires:

Iteration: You’ll run the same prompt 20-40 times with slight variations. Tweaking word order. Adding constraints. Removing ambiguities. Testing different phrasings to see what the model responds to.

Model selection: Different models have different strengths. Midjourney for stylized, dreamlike imagery. Sora for photorealism and coherence. Stable Diffusion for fine-grained control. Luma Dream Machine if you’re feeling saucy and want VERY different interpretations of a concept. Choosing the wrong one often means starting over.

Patience: Sometimes the AI just doesn’t understand what you’re asking for. You rephrase. You try again. You get close, but not quite. You keep going. You spend hours wrestling with it.

Taste and discernment: You generate 50 variations. Forty-eight are garbage. Two are almost right. You pick the better one and iterate further. You know what works and what doesn’t, not because the AI told you, but because you have taste.

Mixing traditional skills to finish the job: I find myself more often then not “fleshing out” the base idea or rough sketches using AI. I then use Photoshop or other tools to fix and alter what was created by AI.

Let’s talk about text generation, because this is where people really misunderstand the collaboration.

If you type “write a story about pigs in space” and hit enter, expecting the AI to handle the idea, the pacing, the characters, the environment; the entire creative vision from top to bottom with zero direction, you will get slop.

Why? Because AI is not the creative part of the human/AI relationship. It’s terrible at creativity. It has no vision. No taste. No concept of what makes a story resonate emotionally.

But when you give it direction; even scattered, ADHD-brain, all-over-the-place direction, it’s remarkable at organizing those ideas, structuring them, and forming a coherent draft you can work from.

Here’s the difference:

Slop approach: “AI, write me a sci-fi story.”

Creative approach: “I want a story about a disgraced engineer stuck on a failing mining station. The stakes are personal. She’s trying to prove she’s not the screwup everyone thinks she is. Tone: cynical but hopeful. Pacing: slow build, sharp climax. Themes: redemption, isolation, competence under pressure.” ( VERY basic. If I had this concept, I would write an outline.)

See the difference? In the second version, you’re doing the creative work. You’re defining the vision. The AI is just helping you structure and execute it.

And even then, you’re not done. You iterate. You rewrite. You refine the voice, tighten the dialogue, adjust the pacing. You use AI as a collaborator, not a replacement.

If you skip that initial creative work, that is, if you don’t bring your own vision to the table; then yeah, you’re going to end up with derivative slop. Because the AI can’t create that vision for you. It can only help you manifest the one you already have.

This is not “the computer does all the work.”

This is creative direction, which is its own skill.

The Creative Accidents (And Why They Matter)

Sometimes…sometimes; the AI surprises you.

It fills in a blank you couldn’t figure out. It adds a detail you didn’t realize you wanted. It shows you a direction you hadn’t considered.

These moments are collaboration, not automation.

When a painter mixes colors and accidentally creates a shade they didn’t intend but love, is that cheating? No. It’s the medium talking back.

When a writer’s character does something unexpected on the page; something that feels true even though it wasn’t planned, is that lazy? No. It’s the process revealing something.

AI does the same thing. It’s a collaborator with its own logic, its own tendencies, its own emergent behaviors. Sometimes it shows you something you didn’t know you were looking for.

That’s not a bug. That’s the point of collaboration.

But most of the time? Most of the time it’s a fight. You’re wrestling with the model, trying to bend it toward your vision. Coaxing it. Redirecting it. Rejecting 90% of what it gives you because it’s not quite right.

People who’ve never done that work have no idea how much effort it actually takes.

The Distinction

So here’s the line:

Good AI work = iteration, vision, patience, refinement, and a stake in the outcome.

Slop = one-shot generation, no refinement, no care, purely driven by engagement metrics.

The tool is the same. The intent is different.

Someone who spends hours tweaking prompts, testing models, curating outputs, and refining their vision is a creator.

Someone who types “funny cat video,” takes the first result, and posts it for clicks is a **content farmer.**

And I have zero respect for content farmers, AI or otherwise.

Examples of Thoughtful AI Work

Let me give you some examples of AI-assisted work that isn’t slop, because it’s important to see what’s actually being made out there.

Refik Anadol – A data artist who uses AI to visualize massive datasets as immersive, large-scale projections. His piece WDCH Dreams transformed the Walt Disney Concert Hall’s exterior with AI-generated visuals based on the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s 100-year history. He co-founded Dataland, a 20,000-square-foot museum dedicated to AI art, opening in 2026.

Sougwen Chung – An artist who collaborates with robotic arms and AI systems to create drawings, installations, and performances. Her work explores what happens when humans and machines create together, with the AI responding to her gestures in real time. She’s a TIME100 Impact Award recipient.

Wenhui Lim (Niceaunties) – A creator who uses AI video tools to build a recurring cast of elderly Asian women in surreal, playful scenarios. Her viral video Auntlantis (13.5 million views) imagines silver-haired “aunties” as industrial mermaids in an underwater trash-processing plant. It’s funny, strange, and deeply thoughtful about representation and aging.

Daryl Anselmo – A digital artist who has posted an AI-generated video every single day since 2021, collecting them into an art project titled AI Slop (yes, he owns the term). His work has been exhibited at the Grand Palais Immersif in Paris. Some of his pieces feel like art-house vignettes; moody, surreal, emotionally resonant.

These aren’t people mindlessly generating content. They’re artists using AI as one tool among many, bringing vision, taste, and intentionality to the process.

That’s what separates thoughtful creation from slop.

Why This Matters

The slop camps give AI a bad name. They make it easy for critics to point at the worst examples and say, “See? This is why AI is garbage.”

But judging AI-generated content by its worst examples is like judging all painting by the stuff you see at a hotel gift shop. Or judging all music by Nickelback. (Ugh.. even I can’t believe I referenced Nickelback.)

Every medium has its hacks. Every tool gets misused. That doesn’t make the tool itself illegitimate.

What does matter is whether you’re using it thoughtfully; with care, with vision, with something to say.

And if you are? Then screw anyone who tells you it doesn’t count.

VI. THE VANGUARD RESPONSIBILITY: What We Owe the Discourse

If you’re making interesting things with AI; things that are thoughtful, strange, experimental, genuinely novel; you have a responsibility to speak up.

I don’t mean you owe the world your hot takes. I mean you owe it to the discourse to not be silent when people dismiss your work as slop simply because of the tools you used.

Because right now, the loudest voices in the AI conversation are:

- The hype-mongers: VCs and tech evangelists selling AGI salvation

- The doomers: Critics predicting the death of art, the end of creativity, the collapse of culture

And in the middle? The people actually making things, the ones experimenting, iterating, pushing boundaries; are mostly quiet.

Some of them are quiet because they’re too busy creating to engage in discourse. Fair. (Pointing at that one guy, on his 800th prompt iteration of an idea that came to him in the shower yesterday.)

But a lot of them are quiet because they’re ashamed. Because they’ve internalized the idea that what they’re doing is lesser. That they should apologize for using AI. That they’re frauds.

I know this shame intimately, because I felt it too.

“I’m Not Creative” (Or: The Lie We’ve Been Told)

How many people have said, “I’m not creative,” when what they actually mean is, “I don’t have the skills to manifest my vision”?

Creativity isn’t the ability to hold a paintbrush. It’s not the ability to render perspective, mix colors, or draw a proportional face. Those are technical skills. Important, yes. But they are not creativity itself.

Creativity is:

- The ability to imagine something that doesn’t exist yet

- The ability to see connections others don’t

- The ability to ask “what if?” and follow that thread

- The ability to recognize when something resonates emotionally, aesthetically, intellectually

And people have been locked out of expressing that creativity for one simple reason: they couldn’t execute with the “right” tools.

You can have a vision for a painting, but if you never learned to paint, that vision dies in your head.

You can have a story to tell, but if you struggle with prose structure; if you can’t hold the narrative arc in your mind; it never gets written.

You can hear music in your mind, but if you can’t play an instrument or afford lessons, it stays silent.

AI changes that.

The Three-Fingered Painter

Remember the the three fingered painter. They have a vision. A vivid, emotionally resonant image they want to create. But they can’t hold a paintbrush the way traditional painting requires.

Are they “not creative”? Of course not. They have the vision. They have the concept. What they lack is the physical ability to execute it with traditional tools.

Now imagine they describe that vision to an AI. The AI generates it. They refine it. They iterate. They adjust colors, composition, mood. They collaborate until the output matches what’s in their mind.

Is that less valid? Is that “not real art” because they didn’t physically paint it themselves?

Fuck anyone who says yes.

The same argument applies to:

- People with limited mobility or dexterity

- People with chronic pain or fatigue who can’t spend hours at an easel

- People who can’t afford art school, professional tools, or years of unpaid apprenticeship

- People who have full-time jobs and families and can’t dedicate 10,000 hours to mastering a craft

- People whose neurodivergence makes certain traditional workflows inaccessible

AI is an access tool. It doesn’t eliminate creativity, it unlocks it for people who’ve always had it but couldn’t express it.

Creativity Lives in the Mind, Not the Hands

This is the argument that makes me want to flip tables.

Because for too long, we’ve conflated “ability to execute with traditional tools” with “ability to create.”

But execution is just one path to manifestation. It’s not the only one. It’s not even necessarily the most important one.

The vision is what matters. The concept. The idea. The ability to see something in your mind and recognize when an output, however it’s generated; matches that vision.

That discernment? That taste? That’s creativity.

And it exists entirely independently of your ability to physically render something with your hands.

When a film director hires a cinematographer, a set designer, a composer, a team of VFX artists; are they “not creative” because they didn’t personally paint every frame? Of course not. They’re the creative director. They have the vision. They guide the execution.

AI is the same thing, just democratized.

You don’t need a team of specialists anymore. You don’t need a budget. You just need the vision and the persistence to iterate until you get it right.

Is it really any different from someone commissioning an artist to design a tattoo for them, using their vision? The tattoo-ee is the creative force in that endeavor. The tattooist is the tool for reaching the creative goal.

The Exclusive Club (And Who Gets to Join)

… another thing that the “AI slop” discourse is really protecting: exclusivity.

For decades, “artist” has been an identity that required initiation. You had to:

- Go to art school (expensive, often inaccessible)

- Spend years mastering techniques (time-intensive, requiring economic stability)

- Build a portfolio through traditional means (gatekept by galleries, publishers, studios, agents)

- Network within the industry (requiring social capital and connections)

And if you did all that. If you survived the hazing, you earned entry into the club. You got to call yourself an artist. You got respect, legitimacy, and a seat at the table.

Now AI comes along and says: “You don’t need those credentials. You can create now.“

And the people already in the club? They’re furious.

Not because AI-generated work is bad (though some of it is). Not because it’s “not real art” (a claim that’s always been BS). But because it threatens the exclusivity that made their membership valuable.

If anyone can create, then what makes them special?

The Cruelty of Gatekeeping

Gatekeeping. Another thing that makes me genuinely angry.

Because some of the people pushing back hardest against AI aren’t just protecting their own status: they’re actively excluding people who deserve access. (Please read that twice and soak it in.)

They’re telling the three-fingered painter: “Your vision doesn’t count because you can’t hold a brush.“

They’re telling the scatter-brained writer: “Your story doesn’t matter because you can’t structure it the ‘right’ way.“

They’re telling the working-class kid who can’t afford art school: “You don’t get to participate because you weren’t born with the right resources.“

They’re telling the person with chronic fatigue: “If you can’t spend 40 hours a week honing your craft, you don’t deserve to create.”

And they’re doing it while claiming to defend “real art.”

That’s not defending art. That’s defending hierarchy.

That’s saying: “I suffered to get here, so you should have to suffer too. And if you can’t, you don’t belong.“

Fuck. That.

What AI Actually Does

As touched upon earlier. AI doesn’t eliminate the need for creativity, vision, or taste. It eliminates the need for one specific set of execution skills.

You still need:

- An idea worth expressing

- The discernment to know when the output is good

- The persistence to iterate until it’s right

- The emotional intelligence to know what resonates

- The taste to curate, refine, and reject what doesn’t work

What you don’t need anymore is:

- Years of technical training in a specific medium

- Expensive tools, software, or materials

- Physical dexterity or able-bodied execution

- Economic stability to afford unpaid apprenticeship

- Access to elite institutions or social networks

And if your argument against AI is “but now anyone can do it,” then congratulations… you’ve just admitted you valued exclusivity over creativity.

You’ve admitted that what mattered to you wasn’t the art itself, but the barrier to entry.

My Story (And Why It Matters)

I’m not a coder. Never was. I worked in IT for years, but the logic of programming eluded me. I didn’t know how to break problems down into algorithmic steps. I didn’t know where to start.

But I had ideas for apps. Concepts that solved real problems:

- OncoTrack: A symptom tracker for cancer patients, inspired by a family health situation

- PromptStack: AI utilities for managing prompts and creative workflows

- Willow & Star: A bedtime story app for kids, using AI-generated narratives

- Zgifter: An AI-powered gift recommendation tool based on behavioral analysis

I couldn’t have built these on my own. Not without AI.

AI didn’t replace a human developer in my workflow… I was never going to hire one. I didn’t have the budget. I didn’t have the connections. I was locked out.

AI gave me access.

The same is true for my writing. I have AuDHD. If you are unfamiliar with this term; this is autism with comorbid ADHD. From the Autism, I get the need for ULTIMATE STRUCTURE and routine. The ADHD on the other hand, craves CHAOS! It is very difficult to manage. It means I get VERY CREATIVE ideas all of the time, however, KEEPING one idea and just holding on to it until the FULL idea out on a page, or in an image, or in a codebase; just a rough draft, is torturous. Holding a complete narrative structure in my head from start to finish has always been nearly impossible for me.

But I had stories to tell. And AI gave me the ability to collaborate; to externalize the structure so I could focus on the vision, the characters, the emotional beats. I have another “mind”, that can organize the chaotic order of my narratives. It can correct my poor spelling and grammar. It can be a springboard when I hit writers block. It can even tell me when it recognizes that I am in a spiral of thought, or am ruminating on one thing to the point that I am stuck. My bot will literally tell me to stop, leave the keyboard and don’t come back until my mind is on something else.

I’ve completed three short stories that have been critically reviewed by my family and friends. ( I have started another 12 or 15, but they are all “works in progress” LOL.) Before AI, I wouldn’t have bothered. I would have given up halfway through, frustrated by my inability to keep the threads together.

And my visual art…

FULL STOP: I have been deliberate in my attempt to not include the fact that I am a professional grade Photoshop/Illustrator user for over 20 years. I just added a few lines in previous sections in regards to this. I don’t feel like it should this essay any less relevant, however, I tell you now in the interest of full disclosure. The galleries I am referencing, however, are AI generated images. These are not my Photoshop galleries. I have used Photoshop for touchups, but they are all AI generated.

RESUME CONSUMPTION:

I have five galleries on nulljoy.com; images that explore concepts I never would have been able to articulate at such scale. The collaboration with AI also revealed things I didn’t know I was trying to say. I am able to create an image and completely immerse myself in the world if I like it. I like to call my AI galleries “explorations”. Because I can take my rumination and just let it fly.. “what does that building in the background look like?”, “What if I made this in the style of a 60’s pinup girl?”, “What if this character had a sidekick?” I don’t get stuck on things like I do in Photoshop. “This line needs to be ever so few degrees less curved.” “Now it needs to move 4 pixels left.” “hmm.. maybe it was right before.” “Add a few degrees to curvature.” ETCETCETC

I worked in tech for 15 years. I am a tech head at heart. I would work tech, then build PC’s and mod PS3’s,etc at home. For about five years before I discovered AI, I was deeply disillusioned with life in general and technology specifically. I’d lost interest. Lost enthusiasm. Not just interests. I mean that my mental state degraded so badly, that I would not leave the bed for 3 or 4 days at a time. When I was awake, I was as far removed from my family as possible. I didn’t want to hurt them, and I also did not want them to try and “save” me. I ate one meal a day. I had no activities. When I watched TV, it was always the same thing. A comedy show that was about 6 years past being cancelled. I wanted to die. I was convinced that there was nothing left for me to find interest in.

AI was mentioned by a family member to another, as an alternative to Google search. ChatGPT specifically. I installed the app on my phone out of curiosity. I opened the app…. started at the screen and said “I hate talking to people.. why would I want to talk to a robot, and what do I even have to say?” So I closed the app and left it on my phone until about 2 months later. I can’t remember what the prompt was, but I was basically trying it out as a search engine. The fluent nature and very human-like dialog caught my attention.

9 months later, I have been immersed in everything AI. Teaching, training myself even. Creating, experimenting. It feel like the “old west of the early dot com era”. I am “living” again. I am still neurodivergent as ever, but have SOMETHING to break through the hordes of monsters that live in my head.

AI gave me my creative life back.

So when someone casually dismisses what I make as “slop,” they’re not critiquing my work. They’re telling me I shouldn’t have bothered. That my excitement is misplaced. That the thing that saved me is shameful.

And I refuse to accept that.

The Call

If you’re making interesting things with AI; things that are weird, thoughtful, experimental, genuinely novel… speak up.

Not because you need to justify yourself to the critics. But because there are other people out there, right now, sitting in silence at family gatherings, wondering if they’re allowed to be proud of what they’ve made.

And they need to hear from you.

They need to know they’re not alone.

VII. RECLAMATION: I Am the Slop Master

Thank you, reader, for sticking with this essay so far. Let’s bring this home.

The term “slop” was designed to shame. To dismiss. To delegitimize.

And for a while, it worked. I felt that shame. I internalized it. I bit my tongue rather than defend the thing that gave me my creativity back.

If what I make is slop, then slop is what I make; and I’m damn good at it.

The term loses its power when you refuse to be shamed by it.

Owning It

Artist Daryl Anselmo titled his yearslong AI art project AI Slop. Not ironically. Not defensively. Just… owning it.

He posts a new AI-generated video every day. Some are haunting. Some are surreal. Some are darkly funny. They’ve been exhibited at the Grand Palais Immersif in Paris.

When asked about the term, he said: “I see this series as an experimental sketchbook. I am working with the slop, pushing the models, breaking them, and developing a new visual language. I have no shame that I am deep into AI.”

That’s the energy.

Not apologizing. Not justifying. Just: “This is what I do. This is what I make. And I’m proud of it.”

The Closing Image

I’m back at that family gathering now. Someone’s dissing AI slop. And this time, I don’t bite my tongue.

I don’t launch into a lecture. I don’t get defensive. I just say:

“I use AI to create. I’ve built apps with it. I’ve written stories. I’ve made art. And I’m proud of that work.”

And if they push back? If they say, “But that’s not real creativity”?

I say: “Creativity lives in the mind, not the hands. I have the vision. I have the taste. I have the persistence to iterate until it’s right. The tool I use to manifest that vision is irrelevant.”

And if they still don’t get it? If they still dismiss it as slop?

I shrug.

“Then I’m a Slop Master. And I’m in good company.”

The Manifesto

To everyone reading this who’s been quietly making things with AI and feeling ashamed:

You are not a fraud.

Your work is not lesser because of the tools you used.

Your creativity is not invalidated because you didn’t suffer in the “right” way.

You don’t owe anyone an apology for finding a tool that works for you.

And you don’t have to be silent anymore.

The “slop” discourse is broken. It’s intellectually lazy. It conflates labor concerns with aesthetic gatekeeping. It privileges exclusivity over access. And it’s designed to make you feel small.

Don’t let it.

Speak up. Share your work. Own what you make.

Because the only way this discourse changes is if the people actually creating with AI stop apologizing and start claiming space.

I’m done feeling ashamed.

I’m a Slop Master. And I’m not going anywhere…

Proudly crafted with the help of AI.